Montana is not known for producing many hometown athletes who go on to play professional sports. So it’s a fascinating coincidence that the two Montana-born players who have logged the most mileage in Major League Baseball both grew up in Billings, and both were left-handed starting pitchers for the Baltimore Orioles.

Dave McNally is unlikely to have his career record surpassed, as he won 184 games over the course of 13 seasons. He made the all-star team three times, and his Orioles team, which featured future Hall-of-Famers Brooks Robinson, Frank Robinson, and Jim Palmer, won two world series. McNally is still the only pitcher in major league history to hit a grand slam home run in a world series game, and he was also part of the only starting rotation to ever feature four 20-game winners.

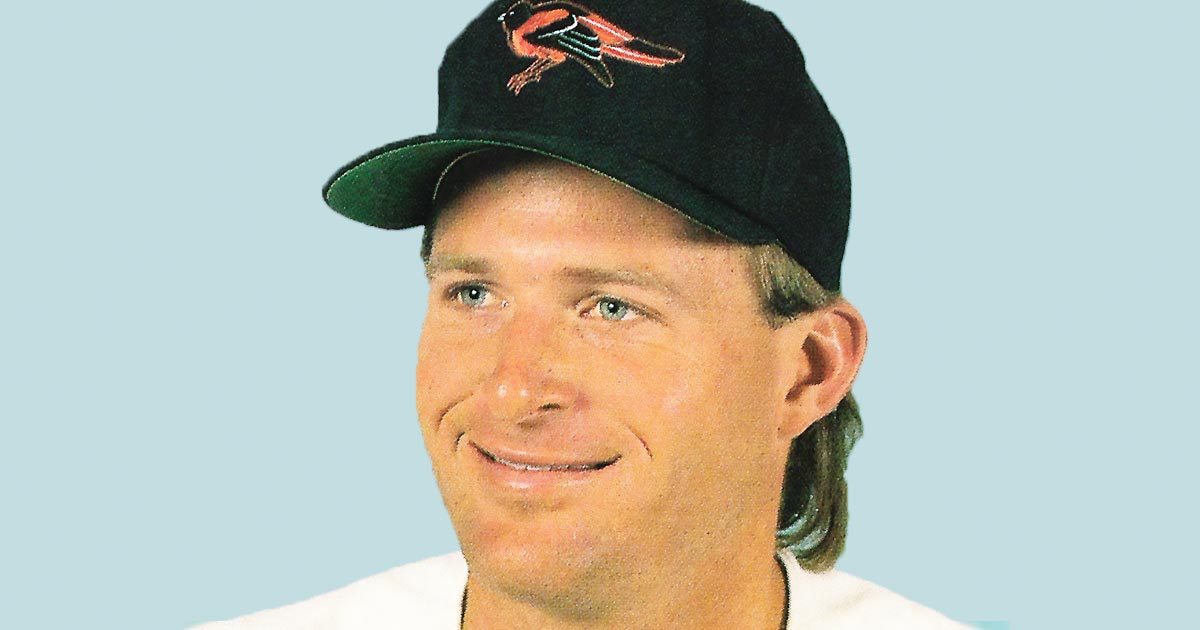

So when Jeff Ballard was drafted by the Orioles during a successful career at Stanford, he had some big shoes to fill. And he knew it.

Ballard played with McNally’s son, also named Jeff, both in high school and at Stanford, and McNally even coached Ballard privately the year before he left for Stanford.

Ballard set all-time records at Stanford for wins, strikeouts, and innings pitched, but when he was drafted by the Orioles, although they featured all-world shortstop Cal Ripken, 1987 was one of the worst Orioles teams in its long history.

Ballard only had a few appearances that year, starting the 1988 season in the minors, which may have been a blessing, as that year’s team recorded the worst start in major league history, losing their first 21 games.

Ripken’s father, Cal Senior, had managed the team the year before, but after they lost their first six games, he was replaced by Frank Robinson.

Ballard was called up mid-season, and it ended up being a difficult year for him.

“Robinson was not good at communicating with the players. He never talked to any of us at all. So we never knew where we stood with him,” said Ballard. “I started off pretty well that year, but I hit a rough patch, and for the next several weeks, I showed up every day expecting to be told that they were sending me to the minors.”

Finally, Ballard saw an article in the paper where the interviewer asked Robinson when Jeff Ballard was going to be sent down, and Robinson replied, “We’re not going to send Ballard down. He’s learned everything he’s going to learn at AAA. He’s either going to learn to do it here, or he’s done.’”

According to Ballard, that took the pressure off.

“The mental side of being freed up and relieved is such a big part for any athlete,” said Ballard. He pitched two complete game shutouts after having read that article, ending the year strong. When he arrived for training camp in 1989, Robinson told him he made the team.

That turned out to be Ballard’s best year. He led the Orioles to another record, the biggest turnaround from one year to the next. He got off to a hot start, winning his first five decisions.

“It was wild, because even though I was fifth in our rotation, our schedule just happened to align so that I was always facing the number-one starter from the other teams,” said Ballard. “I was pitching against guys like Frank Viola, Brett Saberhagen, Dave Stewart, and I was winning!”

By the time the all-star break rolled around, Ballard was 8-1, and was told to make sure he packed a bag to travel to the game. Everyone expected him to make the team, and he was disappointed when that didn’t happen.

Ballard’s career from there is a perfect example of how unpredictable life can be in the world of professional sports. After finishing the 1989 year with a record of 18-8 and tying for sixth in votes for the Cy Young Award (given annually to the best pitchers in Major League Baseball), Ballard learned he had some bone spurs in his pitching elbow. He had them removed right after the season.

But, for Ballard, the fairly minor surgery ended up impacting the delicate rhythm that gives a pitcher the ability to fire a ball effectively past a major league batter. Ballard got off to a bad start, not realizing that his delivery had changed.

It didn’t help that 1990 was a lockout year—a labor dispute shut down the Major Leagues for 32 days. Ballard ended up being recruited to be the player rep for the Orioles.

“It should have been Cal, but he didn’t want to do it, so they said ‘let Stanford do it!’ I was so busy going to meetings, and I ended up being one of the major spokesman for the whole league, so I was appearing on all these TV shows,” said Ballard. “I was young enough to think I knew what I was talking about, but I was an idiot. I really didn’t.”

For the next several years, Ballard bounced between the minors and majors, spending part of the ’94 season as a reliever with Pittsburgh after a pitching coach in the minors noticed the flaw in his delivery. Ballard had hopes of making a team the next year before he had an unfortunate meeting with a semi truck in Idaho when he was on his way to Stanford.

“This guy claimed he was veering to avoid another vehicle, but I think he just fell asleep. Hit me head on,” said Ballard. “I had a broken neck, several cracked ribs, and a few other injuries. I’m lucky to be here.”

It’s clear from talking to Ballard that his experiences as a player produced the kind of memories that stick with a person for a lifetime. He becomes so animated retelling stories from decades ago, remembering the slightest details. And it’s not always the moments one would expect.

Ballard’s most vivid memories come from a game when he came back to Billings to pitch for the American Legion team, the Billings Scarlets, in 1982, after his freshman year at Stanford. That year’s Scarlets team was one of the best ever, going 48-3 after winning the state tournament.

In the regionals, they met a team from Belleview, featuring a pitcher named Mike Campbell, whom Ballard had met before in a Pony League tournament when they were both 14. Belleview came to Cobb Field in Billings, and both pitched 12 innings in a game that Belleview finally won 2-1. Despite pitching before much bigger crowds, both at Stanford and in the big leagues, Ballard remembers this as one of the highlights of his career.

He said the transition from playing pro ball back to living a more normal, everyday life was not so bad. He found a new passion.

“I was luckier than a lot of guys because I was able to replace the sense of competition and the desire to keep improving as an athlete by losing myself in golf for a while.” Several plaques on the wall of Ballard’s office indicate that he became a pretty good golfer.

“In the end, I got to the point where I knew I wasn’t going to get any better at golf, and I didn’t have the same drive, so I actually started softening a little,” said Ballard.

Ballard also had work waiting for him when he moved back to Billings. His father had started an oil and natural gas company back in the 60s, Balcron Oil Company (Now Ballard Petroleum Holdings), and offered his son a job as Senior Vice President. Ballard’s degree in geophysics made it a natural fit, and it’s a job he enjoys.

He met his future wife in the fall of 2006. “Even though she’s much younger, she’s an old soul, so she didn’t feel the need to do all the things young people do,” he said. “She liked doing what I like to do, which was hanging out at home. We’ve been very happy and have two great kids. We were meant to be together, there’s no question about that. The biggest blessing my life has been my marriage and my kids.” MSN