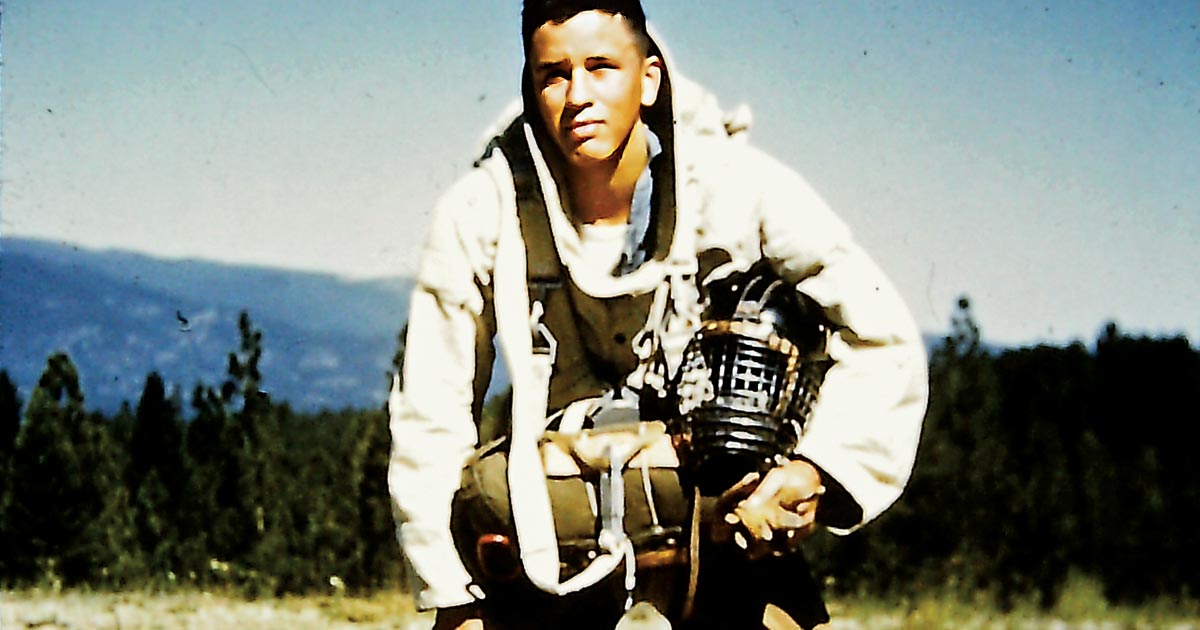

Before dawn on the morning of April 17, 1961, my father stood outside the door of a jump plane at a clandestine CIA airbase on the coast of Nicaragua. He had been up all night, helping 170 Cuban exiles don their parachute rigs and equipment. Speaking no English, he and a fellow smokejumper from Missoula, Mont., relied on hand signals with the men, helping cinch straps, fasten buckles, and secure helmets. He slapped each man on the back for good luck as they boarded the plane.

Most of the men would make their first parachute jump ever at dawn. Most wore surplus WWII parachutes and carried weapons of the same vintage. Before the end of the day, after planned air support from the United States was abruptly halted, most of the men were either dead or being held as prisoners of war by Fidel Castro’s military.

My father would return to his young wife and first-born son a month later. Forbidden to share any details, he simply expressed anger and betrayal. He told her only, “I slapped men on the backs and sent them to their death.”

I would not learn any of these details until 50 years later. While I had an inkling in high school during the 1980s that my father had been involved—somehow—in the Bay of Pigs invasion, he had refused to share many details. He said only that the CIA often recruited smokejumpers from the base in Missoula.

“I took an oath,” he told me one day while I pestered him for more details. “And it included the words ‘under severe penalty of law.’”

My father died in 1990 of a brain tumor, having kept his oath mostly intact. But about a year before his death, knowing his time was running short, he showed me a large manila envelope he kept tucked in his desk. Inside, he told me, were clues that might be helpful if I really wanted to find the truth after he died. “I kept a notebook, you know,” he told me.

For as long as I can remember, my dad carried a small notebook tucked in his shirt pocket. It was a habit I believe started when he was a smokejumper in the 50s and 60s—to keep track of all the details of fires he’d jumped into.

It would be another two decades before I would pay any attention to that envelope, which I’d kept in my attic in Helena. Inside was a faded white business envelope from the “Civil Air Transport.” Inside the envelope were 11 pages from one of my dad’s notebooks, stapled together. They were filled with simple notes about train tickets, plane rides, meals, and hotels in Washington, D.C., and having received what would have been a fairly substantial amount of money at the time. There was also a simple white crucifix inside a frame my father had made.

It launched what became a nearly three-year project to find out what my father did in 1961. My quest included a Freedom of Information request to the CIA, which responded six months later with the expected cliché that the agency “cannot confirm or deny the existence or non-existence” of information about my father. I reached out to dozens of smokejumpers from that era, hoping they could provide me more clues about what my father did.

In the end, I not only learned the full story of my dad’s brief stint as a CIA contractor, but I met and interviewed the fellow jumper who accompanied him.

My dad and his friend Cliff were recruited in March 1961. Told they could make easy money for a month or two of secret work, both said yes. My dad withdrew from the University of Montana and told his wife not to worry.

His notebook and my interview with Cliff told the rest of the story. They left Missoula on a train to Spokane then flew to DC, spending a week being briefed by CIA operatives at different hotels in town. Travels were paid for with checks or cash my father was handed. Each man was given a new, fake identity. My father, William Z. MacDonald, became William C. McCusker.

They flew to Eglin Air Force Base and then a mothballed airbase in the Florida swamps, where they met members of The Brigade 2506, the Cuban freedom fighters who would be the invasion force.

The two spent a week at a CIA base in Guatemala before being secreted to another CIA base in Nicaragua. Here, they learned they would be among a handful of Americans who would rig parachutes for jumpers, do final equipment checks, and help each man aboard a plane.

A Catholic priest led a prayer for the invaders, then blessed my father and Cliff and handed each a small white crucifix. My father had held onto his. Shortly after returning to the US, my father would receive the balance of his payment—more than $2,000; a hefty sum in 1961.

Cliff would tell me the two never spoke about their trip. “I think we were all proud that we tried to help,” Cliff said. But, he added, the government’s decision to pull its support in the middle of the invasion felt like a betrayal. “We didn’t understand what happened. We didn’t understand why,” he said. “We were all certainly bitter.” MSN