By BERNICE KARNOP

One of the first things west-bound travelers on I-94 see after crossing into Montana from North Dakota, is a nine-foot tall bronze image of Pierre Wibaux, (say WEE-bo). The striking figure sports a handlebar mustache and wears a fringed buckskin jacket, chaps, a big Stetson hat, and cowboy boots. One hand holds a pair of field glasses and the other grasps a rifle. At his feet lies a coil of rope. His gaze stretches northwest over the town of Wibaux, toward his W-Bar ranch, 12 miles out.

Wibaux was son of a prosperous French family prominent in the textile and dye industry. Born in 1858, he was educated and trained for the family business. When he went to England to study their textile industry, he heard about opportunities for cattle ranching in the American west. To his father’s disappointment, in 1883, he traded the comforts of home and the textile industry for the life of a cattle baron in the Montana Territory. He spent that winter in a dugout near Beaver Creek. The next year he brought his wife, Mary Ellen, from New York. It’s said that they ate Christmas dinner in the sod house with a dirt floor, wearing full evening dress.

They were not the only privileged people who embraced the hardship and hard work required to be ranchers. Contemporaries included fellow Frenchman, the Marquis de Mores, in Medora, North Dakota, and Teddy Roosevelt, who would become President of the United States.

Before 1895, the town of Wibaux, was called Mingusville for the two of the original residents, Minnie and Gus Grissy. Teddy Roosevelt visited Mingusville, according to David McCullough’s biography, Mornings on Horseback. In a bar incident, “he stood up and in a quiet, businesslike fashion flattened an unknown drunken cowboy who, a gun in each hand, had decided to make a laughingstock of him because of his glasses. Theodore knocked him cold with one punch.”

Most people were okay with the name Mingusville. Pierre Wibaux, however, drew up a petition to have it changed. According to Marlene Welliever, who has lived all of her 81 years in Wibaux, and who was curator at the Wibaux Museum for 14 years, Wibaux gathered signatures at one end of the street, then rode his horse to the other end of the street where the same people would sign it again.

Wibaux ran vast herds of cattle, longhorns brought up from Texas. Some sources say he had as many as 35,000; other sources claim he had 75,000. His operation made Wibaux the biggest cattle shipping point on the Northern Pacific line. Pierre Wibaux’s cowboys staged the first rodeo in Wibaux to entertain visiting French aristocrats.

During the disastrous winter of 1887, as many as 70 percent of the open range cattle perished. This is the event immortalized by Charlie Russell’s famous sketch of a skinny cow in a blizzard, titled Waiting for a Chinook. While the winter ruined many, Wibaux remained optimistic. He went back to France, borrowed money, and bought the sturdiest surviving stock from his neighbors. Then he raised the new crop of alfalfa, and fed his cattle over the winter.

When homesteaders arrived in such numbers to put an end to the open range, Wibaux diversified into banking and gold mining in Montana and to other enterprises around the world. He traveled and spent time in France, but his heart remained in Montana.

He died in 1913 in Chicago at age 55. Although his wife and only child lived and were buried in France, he requested that his remains be brought back to Montana. His ashes are buried beneath the town statue.

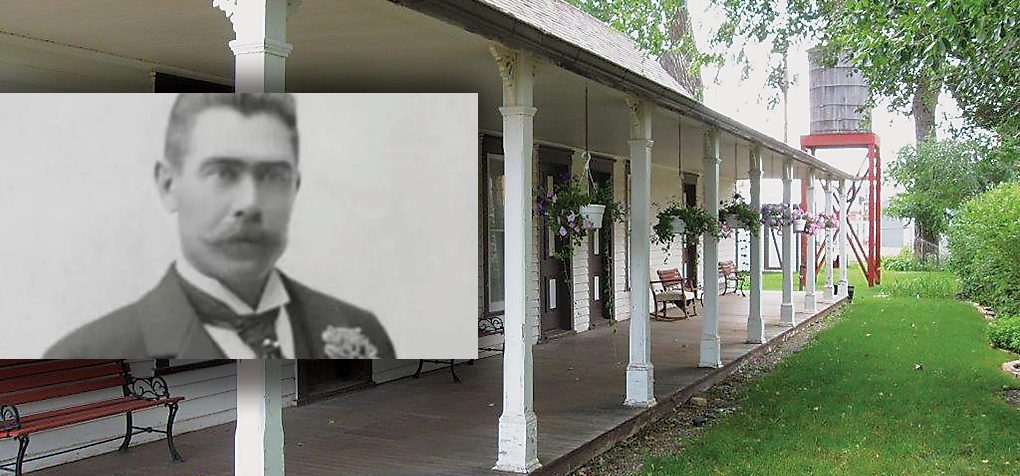

The Wibaux ranch house anchors a museum complex that helps interpret his life. Marlene Welliever said they made it as much like the original late 1800’s one as they could. Welliever fondly remembered when more than a dozen Wibaux relatives from France visited the museum a few years ago. The complex includes a livery stable containing a Rumley tractor and early tools, a shoe shop, and a grocery store. The 1900’s barber shop boasts a reproduction of the first indoor bathroom in the area, and a rail car from the 1964-65 Montana Centennial Train that went to the World’s Fair in New York and is chock full of Montana memorabilia. The museum is open from May to September.

Wibaux business district includes buildings on the National Register of Historic Places, including Saint Peter’s Catholic Church. Pierre Wibaux’s father paid to have it built in 1885, so his family would have a church to attend. Originally a wood frame building in Gothic Revival style, it was enlarged in 1931, and the exterior was covered with colorful, native rock. Notable are the stained glass windows and ivy growing over the walls.

Wibaux is still a cowboy community with a population of no more than 500 people today. The local high school’s six-man football team, appropriately called the Longhorns, is one of the best six-man football teams in the state. The area draws hunters and fishermen by the scores. The first Travel Montana Visitor Center on I-94 is situated just off Interstate 94 at the exit on top of the hill.

In 2008 Jim Devine and Sandon Stinnett opened the Beaver Creek Brewery, which Welliever says brings a lot of people to town. Their Halloween party “looked like the 4th of July celebration,” she said. They brew more than a dozen different beverages, including Wibaux Gold, Paddlefish Stout, and Rough Rider Wheat. They also make a non-alcoholic root beer from their secret recipe. Their web site advises, “Try it with two scoops of Montana-made Wilcoxson’s Ice Cream.”

Wibaux is a small, gateway-to-Montana town that won the love and loyalty of Pierre Wibaux 200 years ago. Readers who visit the prairies of eastern Montana may understand why.