Downtown Bozeman has never lost its vitality and charm. Twentieth-century architect Fred F. Willson helped shape the look of Main Street by designing extraordinary buildings that remain today. His lengthy career was so productive that, if the buildings he designed were removed, a surprising percentage of downtown Bozeman would disappear.

For example, Willson designed the Commercial National Bank building that was in a classic revival style in 1920. Then in 1972 the owners redesigned the building to look contemporary, and it became First National Bank.

With current new owner Randy Scully and architect Rob Pertzborn at the helm, those alterations are now coming down, and the presently in progress will resurface the elements of Willson’s design. This project has also renewed an interest in the work and life of Willson.

Born in 1877, the humble, even-tempered Willson grew up in Bozeman. His father, Lester Willson, had served in the Union Army. Mustering out as a colonel, he was brevetted brigadier-general, a title that acquaintances used thereafter. In 1867 General Willson arrived in Bozeman, still a crude village, to work with his brother and several others in a mercantile business. Over the years, the others dropped out, leaving Lester to become a prosperous businessman as well as a community leader and state legislator. Willson Street in Bozeman is named after him.

After two years, Lester returned to New York to marry Emma Weeks, an accomplished musician. The two traveled to Montana via steamboat, and Emma’s grand piano came with her. When she played and sang, shadows of people stopping to hear her music would often shroud the windows of their cabin.

The couple had three children, but Fred was the only one to grow to adulthood. In a rich family environment, his mother encouraged him to play the violin, cello, organ, and piano. Years later he played the cello in the city orchestra, and he sang with a quartet for special events.

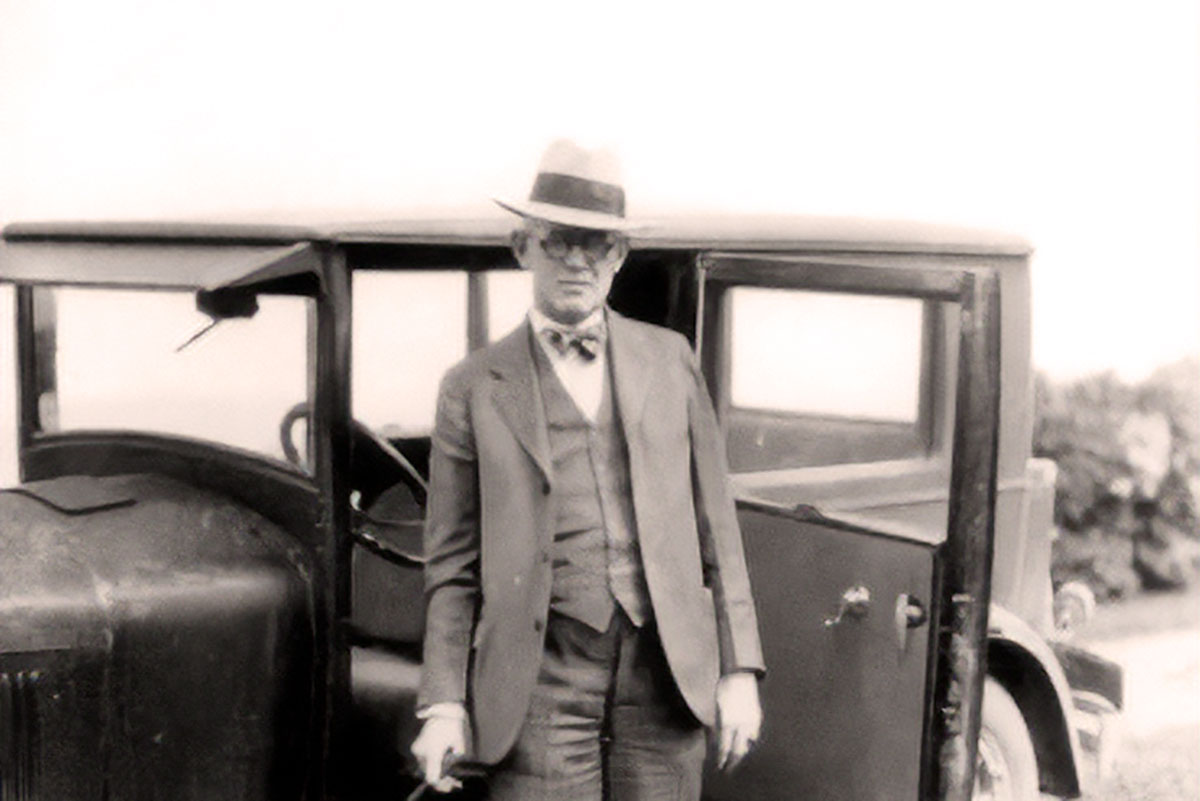

From his father he learned about the business world and how to be a gentleman. Bill Grabow, the architect who worked with Willson and took over the firm after Willson’s death, said he dressed immaculately and never raised his voice.

At an early age Willson became interested in architecture. He was a charter student at Montana State College of Agriculture and Mechanical Arts through his junior year. Transferring to Columbia in New York City, he graduated with a bachelor’s degree in architecture in 1902. Several years later, he furthered his education by studying in Paris and traveling widely to see European architecture.

Willson tended to use the classical design he had studied overseas, but his first priority was the needs of the people who would work or live in the structures he designed.

Instead of trying to make a name for himself, he wanted to help people. If a customer wasn’t happy, Willson simply didn’t cash the person’s check. Years later these uncashed checks were found among Willson’s effects.

He thought being an architect should be considered a public service. His buildings were constructed of inexpensive materials—terra cotta, brick, and stones—but they were materials that have stood the test of time.

Becoming the first native son to become a Montana architect, Willson chose to open an office in the community of his birth and marry Helen Fisher, a young college graduate who was also from Bozeman. “I suspect that my grandmother thought she was marrying into money. It turned out that at times, especially early in the depression and during World War II, architectural work was limited, which was a consternation to her,” Duncan Kippen, Willson’s grandson, said.

Willson was so tender-hearted that he usually left it to his wife to discipline their three children. “My family remembers that he would take his hat and go for a walk whenever our grandmother had to punish a child,” Kippen said.

Sliding the family car into a ditch, Son Lester dented the car. “That was the one time grandfather raised his voice. Years later he said that being angry on that occasion was a regret he had in his life,” Kippen said.

Once Roosevelt’s New Deal kicked in, Willson was so busy, he often went back to work after dinner and worked into the night. During this period, he wrote in his diary that he knew he had a family, but he hardly got to see them.

In addition to the Commercial National Bank building, those Bozeman buildings that bear his mark are the Ellen Theater, Gallatin County Courthouse, Baxter Hotel, the original Armory, and the county high school, which became the middle school that bears his name today. Also, among the 330 structures he designed were buildings at Montana State University campus, structures in Yellowstone Park and southwest Montana, and homes, garages, and apartment buildings in Bozeman. If updates and supervision of projects are included, the number of his projects soared to over a thousand.

One of the last structures he designed was the Soldier’s Chapel located near Big Sky, Mont., on Highway 191 and dedicated by the Story family to one of their own and those who fought in World War II.

After Willson’s death in August 1956, a garbage man discovered a number of Willson’s diaries that contained a record of day-to-day work and family life in a trash can. They were retrieved and are now a valuable part of the Willson papers archived at the Montana State University Special Collections Library.

The Bozeman Chronicle eulogized the feelings of the community with these words at Willson’s death: “One thinks of all things sturdy and strong and secure, when one tries to evaluate properly the life of Fred F. Willson,” MSN