Contains affiliate links

By RANDOPH W. HOBLER

What celebrities do you associate with Montana? Red-blooded Montanans might readily summon up these men in black: Gary Cooper, Evel Knievel, Jeff Bridges.

However, one man deserves 15-minutes of Montana fame, but he sports a name that does not trip so easily off the tongue—Pierre-Jean De Smet.

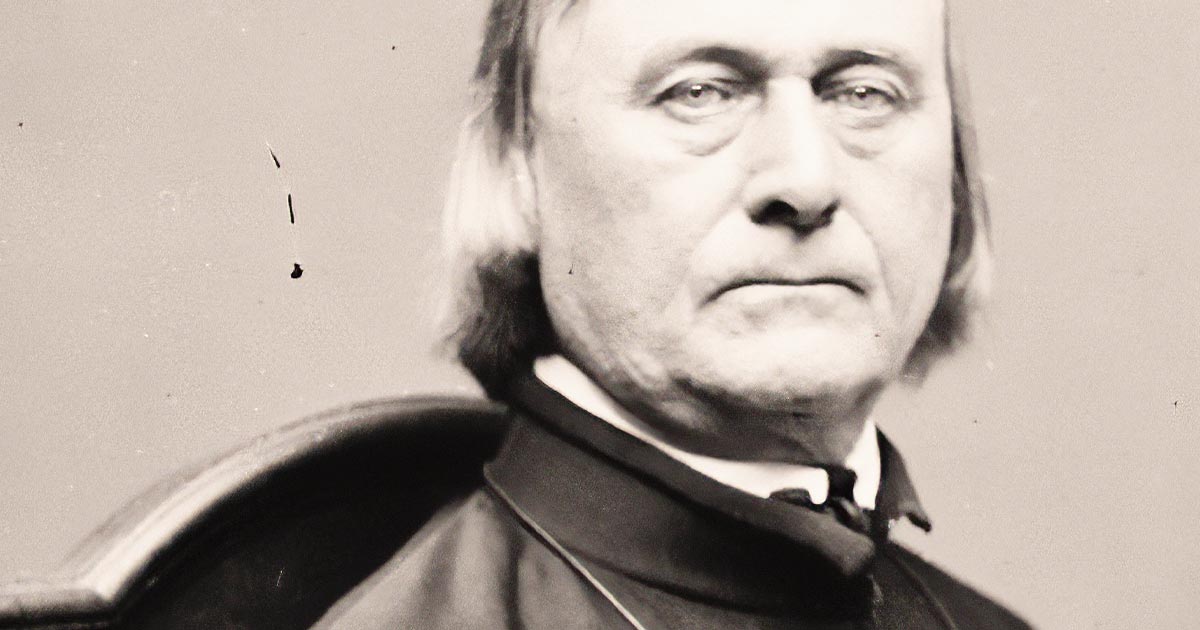

He always dressed in black. In fact, all his fellow Jesuits, spread out over the vast lands of the Louisiana Purchase in the mid-1840s, dressed so consistently in black that the Native Americans referred to them as “black robes.” Pray tell, (so to speak), why should we elevate Father De Smet to the heights of historical celebrity?

De Smet’s claim to fame was that, in 1841, he established the first permanent settlement in Montana, St. Mary’s, nestled in the Bitterroot Valley in the extreme southwest corner of the state. A mere six miles east of Idaho and 29 miles south of Missoula, it made him the founding father (so to speak, again) of Montana.

In the late 1700s, a Salish prophet named Shining Shirt, a Native American Nostradamus, predicted that fair-skinned men dressed in black robes would arrive in the valley to teach the people new morals and a new way to pray. These men, who wore crosses and did not take wives, would bring peace, but their coming would be the beginning of the end of all native people.

Not long after, on the heels of the Louisiana Purchase, in September of 1805, Lewis and Clark trekked through what was to become St. Mary’s. To press on to the West, they had to traverse the Bitterroot range, the longest of the Rocky Mountains, capped by the 9,300-foot-high St. Mary’s peak. This challenge nearly destroyed the dreams of the expedition. By the time they stumbled out of the mountains, they were frozen and near dead from starvation.

In this time frame, nomadic Native Americans, missionaries, and fur traders from the United States, Canada, and France mingled, transacted, partnered, and often intermarried. The fur traders worked cheek-by-jowl with various tribes, trapping martens, otters, foxes, bison, deer, mink and, famously, beavers, whose skins were so coveted for men’s hats.

A new excitement about the “powerful medicine” of Catholicism had reached the Salish of the Bitterroot Valley, and they’d heard of European methods of medicine, not the least of which was how to vaccinate against smallpox.

The Salish were deeply impressed. Thus Father De Smet was thrust into height of the fur trade, between 1820 and 1850.

On A Mission

Born on January 30, 1801 in the Flemish town of Dendermonde (now in Belgium), De Smet was raised speaking Flemish and French. At 19, he entered the Petit Séminaire at Mechelen to pursue his long Jesuit formation. In 1821, first crossing himself before crossing the Atlantic, he took the usually frightening seven-week sail with 11 other Jesuits-in-training, aiming to become a missionary to Native American Indians.

He began his two-year novitiate at a Jesuit mission in Whitemarsh, Md., where he was exposed to English. In 1823, via a two-week journey by stagecoach, he transferred to Florissant, Mo., to complete his theological studies and begin his studies of Native American customs and languages. After seven years of study, he was ordained a priest on September 23, 1827.

Around 1830, De Smet moved to St. Louis, to serve as treasurer at the College of St. Louis. A few years later, he became an American citizen. In the Jesuit’s peripatetic system, Father De Smet then traveled north in 1838 to what later became Council Bluffs, Iowa, to found the St. Joseph’s mission. De Smet worked primarily with a Potawatomi tribe.

In 1831, deeply distressed by so many of their children sick and dying, Salish Chief “Big Face” (Tjolzhitsay) sent a delegation of four Salish chiefs to St. Louis, to ask the black robes for help. Mind you, a one-way trip in those days was 1,625 miles (equivalent to the distance between Portland, Maine and Miami). It was a four-month outing.

They were directed to meet with none other than William Clark of the Lewis and Clarke Expedition, who was then Governor of the entire 69,000-square mile Missouri Territory (formerly The Louisiana Purchase Territory). Two of the chiefs died in Clark’s house. The other two were directed to the office of Bishop Rosati, who assured them missionaries would be sent in the future. Right.

After waiting patiently for four years, in 1835 Chief Big Face sent another five-chief delegation. The Sioux massacred the group. He then sent another delegation in 1837, another 3,326-mile round trip, to no avail.

Figuring they were talking to the wrong people, Chief Big Face sent yet another delegation, this time to De Smet’s St. Joseph’s mission. The group journeyed another 1,200 miles via canoe on the Missouri River.

De Smet met with them and assured he’d go with them to the Salish encampment the following year. Well, they did travel the next year, but for a reason lost in the mists of history—they went to Pierre’s Hole, in what is now Idaho, 300 miles to the south of the Bitterroot Valley. On July 5, 1840, he was greeted by 1,600 Salish tribespeople, 350 of whom he baptized. He then promised that next year he would establish the mission at Chief Big Face’s encampment. After nine years, you can understand why Chief Big Face might have been skeptical.

Finally, Flemish Father DeSmet; Italian Father Mengarini (a linguist and musician); French Father Point (an artist); German Brother Specht (a tinner); Belgian Brother Huett (a blacksmith); Belgian Brother Classens (a man of many talents); three laborers; four horses; and three mules arrived in the Bitterrroot encampment after another 1,600-mile trip, over another four months. Having faced hunger, raging rivers, and treacherous trails, the group scouted for an appropriate settling location in September of 1841.

They wandered for many days and came upon a beautiful valley with rich soil that was protected from the northern winds by two high mountain ridges.

Intent on their mission, they first planted a cross in the ground and second erected a 900-seat church, Montana’s first. Only then did they start building their cabins.

As winter approached, the cold was so intense that the buffalo skin robes they used to wrap themselves at night were frozen stiff and had to be thawed out each morning.

While the first masses were conducted in Latin, Father Mengarini took pains to learn the tribe’s language and began creating prayers in Salish for the tribe to learn.

He also taught songs in Salish and even joined the tribe on a summer buffalo hunt.

De Smet found the Salish to be docile, believing. They appeared joyous about the goodness of the Great Spirit. In short order, he baptized 2,000 Salish. The tribe did not, however, buy into the Jesuits’ attempts to teach them agriculture, as they already had sophisticated assortments of fruits, vegetables, barks, and plants.

De Smet, ever the restless soul, moved on to multiple missions. He traveled around Cape Horn to visit Vancouver, met with nearly every tribe west of the Mississippi, and even once met with Chief Sitting Bull in 1868, to discuss peace negotiations. The American Indians trusted no single person as they did De Smet. One leader described him as “the white man whose tongue does not lie” and “more powerful than an army.”

A spirit of fierce determination on behalf of Native Americans, De Smet traveled across the Atlantic no fewer than 19 times. He traversed nearly every European country and met with popes, kings, and presidents. Over the years, he racked up 180,000 miles (compared to Lewis and Clark’s mere 8,000).

He died at the age of 72 in St. Louis, on May 23, 1873. St. Mary’s itself later became Fort Owen, today’s Stevensville.

As for the Salish of Bitterroot Valley, Shining Shirt’s every prediction held true. On October 15, 1891, the last remnants of the tribe were moved to the Jocko Reservation between Missoula and Kalispell. MSN