By SUZANNE WARING

How do you combine a love of Montana’s history, woodworking, and photography? It sounds incongruous, doesn’t it? For Paul Snyder, 86, these interests fit together like pieces of a puzzle.

In his retirement years, he has become fascinated with the furniture in saloons—especially backbars and front bars.

“Backbars are icons of Montana, and I felt the need to document them,” said Snyder. He knew that time was of the essence because backbars and the companion front bars were fast disappearing from age, fire, economics, population changes, and antique value as home décor. It was time to travel the roads throughout his home state.

Snyder was born in Malta, Mont., went to grade school there, and lived for a time in Ashton, Idaho, and Libby, Montana. His parents moved back to Malta in time for him to attend and then graduate from Malta High School. He enrolled at the University of Montana and earned a degree in history and political science.

From there he joined the Air Force and became a pilot, an interest he’d had from hanging around the Malta airport. When he was honorably discharged, he became a commercial pilot for 27 years with Western Airlines and Delta.

During those years, he and his family lived a short while in San Francisco, but mostly around the Seattle, Wash., and the Whitefish, Mont., areas.

After retirement, he and his wife, Ann, moved to Great Falls, where their daughter lives. Following his love of history, he took on the volunteer job of the maintenance committee for the History Museum.

One interest led to another. He and Ann decided to photograph Montana’s beautiful backbars. They traveled around the state, following leads as to what might be the next “greatest backbar they had seen yet.”

At first it was a hobby, an excuse to take a trip to a suggested destination point. When Ann died in 2018, Paul felt the need for a big project, so he started hunting backbars in earnest. During the ensuing months, he took his photography equipment, along with proper lighting, and put 9500 miles on his car. He tried to photograph the backbars when patronage was meager, such as mornings and early afternoons.

Most of the backbars in Montana were made by the Brunswick-Balke-Collender Company in Chicago, and a few were made by the Phoenix Manufacturing Company in Eau Claire, Wis. Most of the bar furniture was constructed of quarter-sawn, curly birch and golden oak with a mahogany finish.

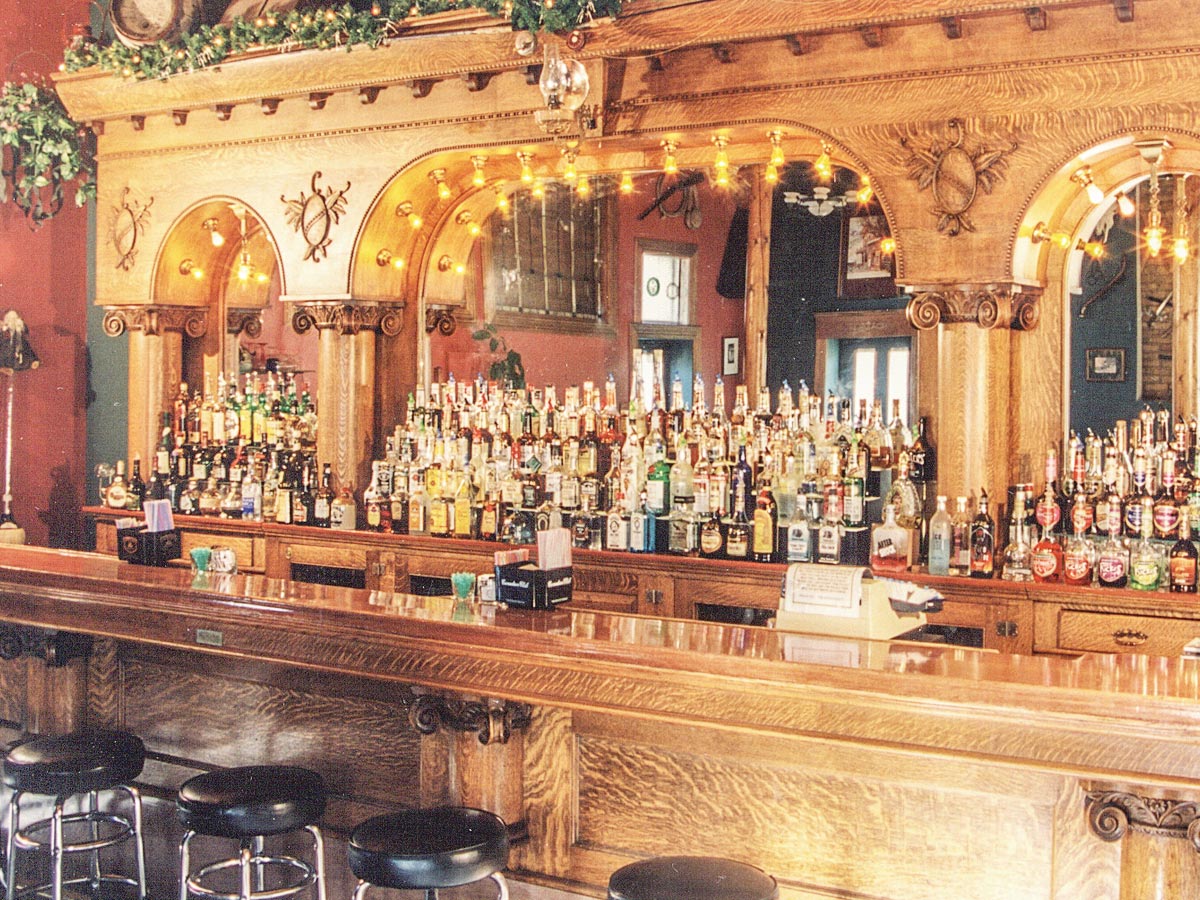

The backbars had mirrors, lighting, hand carvings, solid wood, and a lower counter portion used for storing and displaying liquor. The purpose of the majestic appearance was to draw attention and give the impression of an upscale establishment.

In anticipation of prohibition, the Brunswick-Balke-Collender company quit making backbars in 1912. During prohibition many backbars and front bars were made into soda fountains. Naturally, front bars wore out before the back bars. Of those front bars that still exist, a few have been refinished and coated with polyurethane or lacquer. That is—if the owner recognized that he or she was working with a piece of history.

Snyder’s hunt was more difficult than it might have been years ago. At one time, Livingston with the population of 3000, had 33 saloons. They were places where men conducted business, traded furs, talked politics, cashed paychecks, and found entertainment.

Prohibition put an end to the escalating number of bars in the state. In addition, the drought of the 20s and the realization that 160 acres of land in Montana was not going to support a family caused a population exodus, which reduced the demand for saloons and the income required to keep them operating.

As a result, almost all of the magnificent backbars that Paul researched and photographed were purchased and brought to Montana before 1920. Some were shipped to Montana via the Missouri River on a steamboat.

Although it was difficult to pick favorites, Paul especially highlights the backbars at the Metlen Hotel in Dillon, the Palace Bar in Havre, Norm’s News in Kalispell, and the Montana Bar in Miles City in his book, Make Mine a Ditch, because of their grandiose structure, hardwood, and the intricate hand carvings. Paul emphasizes that these backbars were made before power tools, so all of the intricate carvings were done by hand.

As an example, the Montana Bar is located at 612 Main Street in Miles City. In 1908 owner James Kenney moved the Montana Saloon to this address from next door. Four years later he and his son, George, ordered a Brunswick-Balke-Collender backbar, a front bar, a liquor cabinet, upscale horse-hide booths, and a walk-in icebox to keep the spirits cold.

From the beginning the front bar has had a brass railing where customers can put their foot as they lean on the bar. Interestingly, a bullet hole distinguishes one of the front partitions. It was caused by a gun going off when a customer was checking it.

The backbar is made of three arches with smooth lines, lightly ornamented with classic carved appliques in hardwood, and mirror framing. The heavy, imposing appearance immediately grabs the attention of those entering the establishment. This front and backbar set has been in place for 107 years. MSN

Snyder’s book, Make Mine a Ditch—named after the drink that was originally bad whiskey mixed with bad water—has recently been published by Montana’s Farcountry Press. It is available at the Montana Historical Society in Helena, the History Museum in Great Falls, and through Amazon. If you would like for Paul to give a presentation at your organization on his experiences while compiling and writing this book, contact him at [email protected].