by JEREMY WATTERSON

For 122 years, a Major League Baseball player has rested at Great Fall’s Old Highland Cemetery in an unmarked grave. An effort on behalf of William H. Colgan, the first former player to be buried in the state of Montana, hopes to remedy this in time to unveil a new memorial at the 8th annual Waking the Dead Tour to be held on June 24, 2018.

Billy Colgan was born during the Civil War, in East St. Louis, Ill., on March 19, 1862. A catcher, Colgan saw his first professional action in 1883, playing for his home state’s capital of Springfield. The following year he would appear in 48 American Association games, suiting up for the Pittsburgh Alleghenys in what amounts to his only time in the big leagues. Colgan’s lifetime batting average is a meager .155, low even for the era in which he played, where pitchers were limited to deliveries from below the shoulder, and the rules dictated that a catcher squat beside home bases made of white marble or stone.

The brutality endured by professional catchers of the 1880s was nothing short of barbaric. In an age when masks, chest and leg protections, and often gloves could be seen as sissy stuff, catchers often risked mangling their bodies, with split and broken fingers a regularity. When the everyday catcher was injured, teams often forfeited the game, rather than one of the other position players exposing themselves to the cruelties.

One of the catchers whom Colgan no doubt shared a work space with in 1884, Moses Fleetwood Walker, endured an altogether different level of abuse. Fleet has only recently been credited with being the first African American to play major league baseball, some 63 years before Jackie Robinson broke the sport’s color barrier for good, and the betterment of humankind.

While with Memphis in the spring of 1886, Colgan suffered his worst injury at the hands of a pitcher, but it wasn’t on a ball diamond. Out hunting small game with teammates and friends, Colgan was accidentally shot by his pitcher Bob Black.

According to the Memphis Daily Appeal, the accident happened as Colgan crossed a fence. “Catching hold of the muzzle of his gun, he passed it, butt first, through the crack of the fence, to his companion on the other side. It was accidentally discharged, and a charge of twenty-five buckshot, wads and all, entered his left side near the hip, passing through and lodging under the skin.” Two doctors were called in to successfully remove the shot and dress the wound.

Colgan, whom the sporting papers called “a noted catcher” and “a plucky and conscientious player,” was tendered at least two benefit games. Two months later, he returned to the line-up, catching the very man who had shot him. The healing process may have been quickened by reports that the ladies stand in Memphis was filled to standing room only at every game.

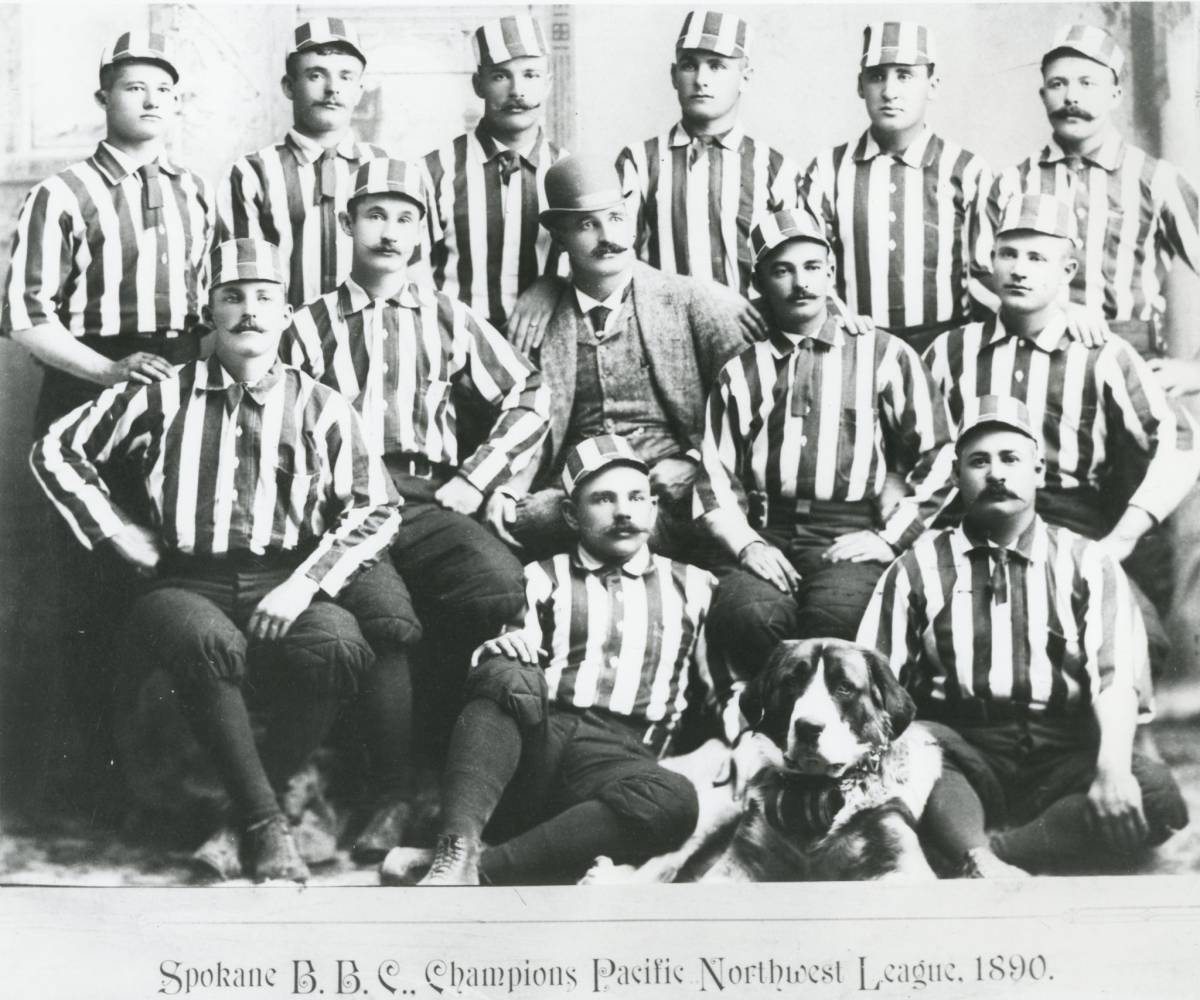

After stints with colorfully named Base Ball Clubs, such as the Kansas City Cowboys, St. Paul Freezers, Milwaukee Brewers (some things never change), Chattanooga Lookouts, East St. Louis Nationals, Evansville Hoosiers, Spokane Falls Bunchgrassers, and Walla Walla Walla Wallas, Colgan found his way onto the ballfields of Montana.

1892 marked the inaugural professional season of baseball in Montana, and Colgan was here. Suiting up first for Butte, he finished the season with Missoula after their catcher badly injured some fingers, and was then bedridden with what was feared to be blood poisoning after being spiked.

Colgan was one of a handful of one-time or would-be big league talents Montanans could witness in the summer of 1892. The most noted stars were an ambidextrous pitcher in a salary dispute with his Cincinnati Red Stocking employers, Tony Mullane, and Clark Griffith, a future Hall of Famer who twice mortgaged his ranch near Craig, Mont., to eventually own the Washington Senators. Griffith, whom Colgan no doubt caught while the two were with Missoula, arrived mid-season from a failed franchise in Tacoma, Wash. Later in life, Griffith detailed a game in which he pitched Missoula past Butte. Missoulians showed their appreciation by showering their pitcher with more oro y plata than he had earned pitching all season in Tacoma.

In 1892, baseball wasn’t the family-friendly product that graces the fields of the four Montana cities that are part of the modern-day Pioneer League, represented in Great Falls by the Voyagers.

As Montana Baseball History co-author Skylar Browning stated in an interview with Montana Public Radio’s Chérie Newman, “Baseball was still a rough-and-tumble sport, and Montana represented that as well as any place. You had leagues that were not very big, as far as the number of teams, but ended up attracting—because there was enough money in Montana at the time—future Hall-of-Fame players. But they were scattered in with brawlers and guys that were just hanging on. So, the professional leagues [often] couldn’t finish the championship series because the teams were not only fighting each other, but fighting the umpires. And games were getting called and having to be decided by forfeit because of the amount of fisticuffs that would end up ruling the field.”

By February of 1893, Colgan was in Great Falls. He wrote a letter to a friend in Anaconda who subsequently informed the local paper that Colgan felt “the Cataract City [a long-lost nickname referring to the large waterfall on the Missouri rather than an eye condition] will make a big effort to get into the proposed intermountain league.”

After this correspondence, Colgan goes missing from newspaper baseball writings, but is presumed to be playing amateur ball in Great Falls, where, according to the Anaconda Standard on August 31, 1894, “the old prospector employed as switchman in the Great Northern yard was promoted to the position of foreman of the inside engines.”

On August 8, 1895, at approximately 1:20 P.M., William H. Colgan was crushed to death while retrieving coal cars from the Boston and Montana smelter on the Montana Central line of the Great Northern Railway. The Boston and Montana Consolidated Copper and Silver Mining Company would merge with the Amalgamated Copper Company in 1901, eventually becoming mighty Anaconda Copper in 1910.

The American West was so young in 1895 that in the report on the coroner’s inquest, the word “Territory” has been scratched out next to the word “Montana” and replaced with the word “State.”

The seven men who testified at Cascade Country coroner Doc Weilman’s inquest described how Colgan was on the tail end of a row of dozen or more train cars that were being pulled across what was discovered to be a partially open switch. When the last coupling crossed the switch, it derailed, resulting in Colgan being pinned between the car he was riding on and a boxcar at a siding. The coroner’s jury ruled Colgan’s death accidental.

News of his death was printed in at least four Montana newspapers, and again detailed in the Anaconda Standard’s 1895 “Montana Year in Review.” The Great Falls Weekly Tribune wrote, “Mr. Colligan (sic) was a strong and hearty man, full of life and energy, strictly sober and highly thought of by the railroad officials and respected and beloved by his fellow workmen and associates. He was greatly interested in athletic sports, especially baseball. He had been connected with a number of clubs and was a professional in this line. His uniform good nature and courtesy made him a favorite in the ball team as well as all who knew him.”

Colgan’s remains were taken to W.C. McBratney’s undertaking establishment. McBratney advertised himself as the man who cremated the first three bodies west of the Rockies. The funeral was held on August 12 at St. Anne’s Cathedral and was paid for by the Switchmen’s union. The half-mile-long cortege was populated by a large number of mourners who saw their friend, the first former major leaguer, to be buried in Montana, off to Old Highland Cemetery, where he resides to this day in an unmarked grave.

A week before his death at the age of 33, Colgan was playing third base for a Great Falls town team against an aggregation from neighboring Sand Coulee when he hit a grand slam. In the home half of the fifth inning, Great Falls tallied seven runs, aided in large part by third baseman Colgan, who, after Great Falls loaded the bases, “gave his bat a cyclone twist and the leather went about halfway over to the B&M addition for a home run.”

Finding Billy Colgan in Montana wasn’t easy, as his career statistics are listed under “Ed Colgan” in Total Baseball, as well as in online statistical databases. His obituary in the Tribune ran under the name Colligan, and his coroner’s inquest had him under the first name of James. Even at Old Highland, his plot was difficult to locate, as records spelled his last name, Cologam.

But he endeared himself to fans and teammates alike during his playing days as a stocky, mustached player with spirited and determined courage, earning such nicknames as Billy, Little Willie, and Shorty.

While Billy Colgan has been a forgotten Montanan for over a century, Norma Ashby is a household name. A Montana television legend, Mrs. Ashby is the chairwoman of the Waking the Dead Tours. History buffs wait for the last Sunday afternoon in June each year for the annual Waking the Dead Tours of Old Highland Cemetery in Great Falls.

This is when they can be transported back in time by three trailers pulled by trucks to visit a select number of graves with storytellers beside them to describe the significant lives of those interned there.

The tours become a living history experience as visitors learn about prominent citizens of Great Falls, such as city founder Paris Gibson and cowboy artist Charlie Russell as well as not-as-well-known lives, such as Ed Shields, who founded the pet cemetery in Great Falls in 1942 and spoke at the funeral of “Shep,” the ever-faithful dog who died in Fort Benton.

“We are always looking for new and interesting people to feature on our tours,” said Norma Ashby, chairman of the Waking the Dead tours. “When Jeremy Watterson, co-author of the 2015 book, Montana Baseball History, told us about the first former big league baseball player buried in Montana, we wanted to know more.”

“Jeremy said his name was Billy Colgan, and he played catcher in the major leagues with Pittsburgh in 1884. He was tragically crushed between rail cars while working on the Montana Central in Great Falls.”

John Rummel at Montana Granite Industries agreed to cut a piece of stone in the shape of home plate to be laid at Colgan’s gravesite. With the help of the internet and phone contacts, Watterson and Ashby are looking to raise the required funds for the stone.

The new marker will be unveiled at the Eighth Waking the Dead tours scheduled for Sunday, June 24, 2018 at 1 and 3 p.m. Watterson will wear old-time baseball attire and recount Colgan’s story as his storyteller.

We’re hoping that through our efforts Mr. Colgan be remembered by fans of the game in Montana and beyond for many more summers to come.

Donations to the Great Falls Cemetery Association are fully tax-deductible and can be mailed with a note to earmark the funds to the Great Falls Cemetery Association;

2010 33rd Avenue South; Great Falls, MT 59405; (406) 454-3731

If you’d like to learn more about Billy Colgan and his merit as a man and Montanan worthy of remembrance, I’d invite you to read my biography written for the Society for American Baseball Research: sabr.org/bioproj/person/52f3b546