From the outside, the clock museum looks like an ordinary jewelry store. It has the same sign hanging over the door it has had for as long as I can remember, which is at least 40 years: BARNES JEWELRY. But if you wander inside, you’ll think you’ve entered another dimension of time altogether.

Nowadays, Barnes’ Jewelry in Helena, Montana is a portal into the past. Oh, you can still get jewelry there, or get jewelry or a watch repaired. But what was once a run-of-the-mill jewelry business has transformed into what I can only describe as a bona fide Curiosity Shop. It’s a little like walking into a museum or carefully curated antique store, but also feels like maybe you’ve wandered onto the set of a Harry Potter film.

The proprietors, Marvin Hunt and Stacy Henry, two of the most engaging characters in Helena, are full of stories they delight in sharing about almost every curio and gewgaw on their shelves. “This is a hands-on operation,” Marvin says. “We want people to touch the stuff.” I see an old dial telephone on the jewelry counter and ask if it works.

“Sure it does,” he says, “Let me call you.” He walks to an even older telephone hanging on the wall, puts the receiver to his ear, cranks it up and suddenly the phone at my elbow rings. When I answer it, Marvin talks into the tube of his telephone, and sure enough, I hear him say “Hello!” Then he shows me an old magneto from yet another phone that he has rewired to supply current to a string of lights hanging above us from a high ceiling. The harder you crank it, the brighter the lights glow.

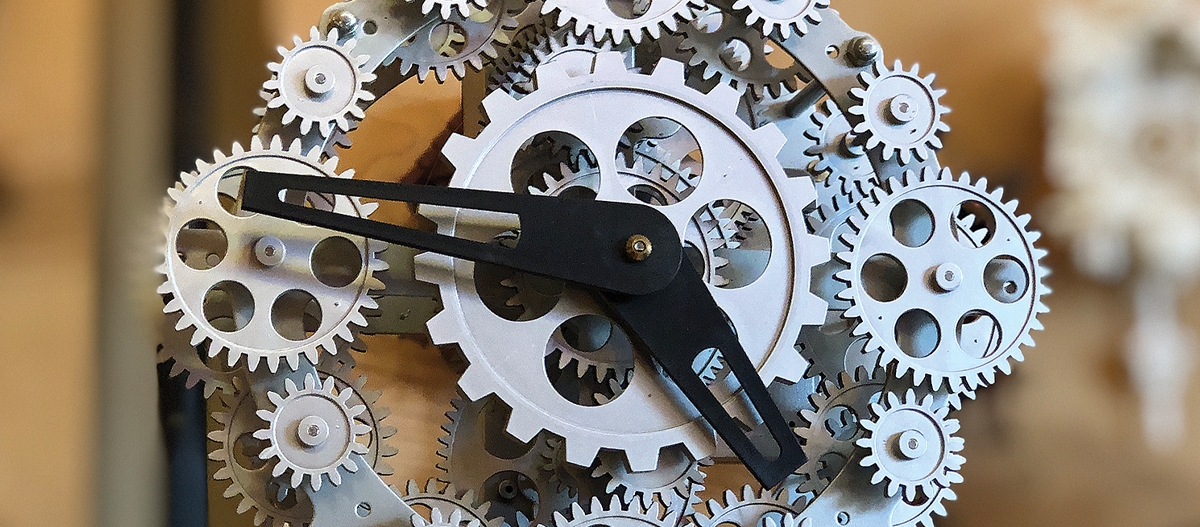

Meanwhile, we’re surrounded on every wall by clocks: hundreds of them, many of them antiques, and it turns out that there’s a story behind every one. Stacy hands me a clock that looks like it was made a couple hundred years ago—the ornate curlicues on the numbers and the bright silver case are clear evidence that this thing is from another era. “See the name of the maker there? That guy is the same person who designed the Seal for the State of Montana!” Sure enough, right below the spindle at the center of the hands, in fine type, is ‘geo. Henren,’ the guy who devised the oro y plata seal.

Clocks, actually, are what brought the two together. “I bought the store from Mr. Barnes in 1991,” Marvin explains. “And Stacy, who collected clocks, started bring them in for repair. I had so much stuff ahead of him to repair, I just pointed to the other workbench and said, ‘You should probably just learn how to fix these yourself.’”

In short order, the two of them began working side by side in the repair shop back behind the front counter—though Stacy now focuses mainly on jewelry, and Marvin handles most of the watch repairs. The shop itself is like a museum within a museum, with banks of fine precision tools poised among loose parts, antique repair manuals, and dozens of watches in various stages of repair.

Marvin brings out a half dozen different pocket watches—his specialty and one of his favorite things to collect (along with antique Christmas Tree lights). He tells me the story of each watch, casually working into the conversation the high points of the history of horology (that’s the word for the study of clocks), deftly popping the tiny machines apart to show me the intricate assembly of precision parts. “By law, in the old days, a railroad watch had to have 17 jewels minimum,” he informs me. “The more jewels, the better the watch.”

But the jewels were not at all for show. Instead, they were tiny little bearings that were practically friction-free, which held the ends of the tiny moving parts that were expertly calibrated to keep perfect time. “A railroad watch had to be incredibly accurate,” Marvin explains. “The watch could not lose more than 2 seconds in 24 hours, no matter what position it was kept in.”

I look at all the watches and a few dozen clocks, and then can’t help but wander around the shop looking at antique gum machines, music boxes, old wind-up Victrolas and 78 phonograph records, and myriad other curious objects from the past. While I’m browsing around, several other customers wander in. A few of them ask about the status of a repair, perhaps, and wander back out to finish other errands, but while I was looking around, at least two folks came in, found chairs, and settled in to hear the stories Stacy and Marvin kept spinning, effortlessly. “I’m just listening in,” said one woman.

I’ve been in hundreds of antique stores, and a fair number of museums in my time, but I’ve never encountered curators who look so happy. The whole time these guys walked me through the inventory of their finest pieces, they were practically grinning, their eyes twinkling, clearly delighted to find someone else who appreciated their passion for what most people would probably consider junk.

“Come back the third Saturday of the month,” Marvin told me when I started to finally leave. “We cook up pancakes in the back.”

As I left, I looked back to appreciate the wall of clocks leading up to a balcony overhanging the jewelry counter, with all kinds of intriguing machines piled everywhere.

I think I will have to go back again soon, not just because I bet the pancakes will be good, but because in three trips to Barnes Jewelry so far, I have not even made it upstairs. MSN